Diabetic Nephropathy from RAAS to Autophagy: The Era for New Players

Rola Nakhoul, Farid Nakhoul and Nakhoul Nakhoul

DOI10.21767/2472-5056.100043

Rola Nakhoul1, Farid Nakhoul2,3* and Nakhoul Nakhoul4

1Faculty of Medicine, University of Szeged, Szeged, Hungary

2Nephrology & Hypertension Division, The Baruch Padeh Medical Center, Israel

3Faculty of Medicine in Galilee Bar-Ilan University, Israel

4Diabetes & Metabolism Lab, The Baruch Padeh Medical Center, Israel

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Farid Nakhoul

Nephrology & Hypertension Division

The Baruch Padeh Poriya Medical Center

Lower Galilee, Tiberias, Israel

Tel: 97246652587

E-mail: fnakhoul@poria.health.gov.il

Received date: June 26, 2017; Accepted date: July 08, 2017; Published date: July 15, 2017

Citation: Nakhoul R, Nakhoul F, Nakhoul N (2017) Diabetic Nephropathy from RAAS to Autophagy: The Era for New Players. J Clin Exp Nephrol Vol.2:43. doi: 10.21767/2472-5056.100043

Copyright: © 2017 Nakhoul R, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Diabetic nephropathy is a leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality worldwide in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The mechanisms behind the pathophysiology of DN are complex and continue to be not fully understood. Both metabolic (hyperglycaemia) and haemodynamic alterations interact synergistically, and have been reported to activate local RAAS resulting in increased angiotensin-2. In spite the early and chronic treatment with converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blocking drugs, the number of patients reaching end stage renal disease and replacement therapy are increasing.

Recently different pathways were proposed to be involved in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy, including the autophagy process, Klotho and the selective agonist vitamin D and his receptor. Under hyperglycemic stress especially in podocytes and proximal convolute tubule cells, there is decrease in the protective autophagic process and increase in cellular damage.

α-Klotho is a multifunctional protein highly expressed in the kidney. The klotho protein has endogenous anti fibrotic function via antagonism of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, which promotes fibrogenesis, suggesting that loss of Klotho in early stage of diabetic nephropathy may contribute to the progression of DN by accelerated fibrogenesis.

The selective vitamin D agonist and his receptor, play a protective pathway in diabetic nephropathy. A key reno-protective function of vitamin D is to reduce albuminuria or proteinuria, major risk factors for CKD progression, renal failure, cardiovascular events, and death. This anti-proteinuric effect and the deceleration of DN progression is mediated primarily via the blocking of the renin angiotensin aldosterone system.

In this review we will discuss the different new mechanisms involved in diabetic nephropathy and future therapeutic agents like the mTorc1 blocker, Rapamycin, that can upregulate the autophagy process, the new sodium-glucose transport inhibitors and Paricalcitol, the selective active vitamin D.

Keywords

Diabetic nephropathy; Autophagy; Klotho; Vitamin D; Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone-System

Introduction

Diabetic nephropathy is a leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality worldwide in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [1,2]. The rapidly rising incidence of (T2DM) worldwide is reputed to affect over 380 million people. T2DM increasingly arises in a younger and more obese population with metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance, leading to decline in renal function and proteinuria, especially in those with uncontrolled blood glucose levels and blood pressure [1-4].

Diabetic nephropathy occurs in up to half of patients with type I or type II diabetes mellitus, and currently accounts for over 45% of new cases of end-stage renal disease treated with replacement therapy. The classic description of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) involved progressive stages of glomerular hyperfiltration, microalbuminuria, overt proteinuria, and a decline in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), leading to ESRD and dialysis. A large minority of patients with type 2 diabetes and reduced kidney function present with normal levels of albuminuria. These findings are consistent with a recent report in which the prevalence of albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes decreased from about 21% in 1988-1994 to 16% in 2009-2014, despite a rise in the prevalence of reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) [4,5].

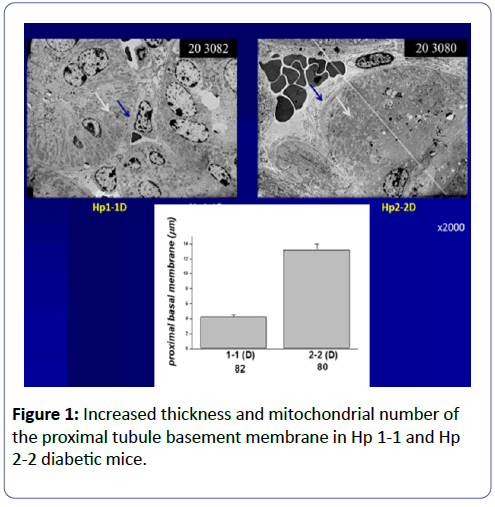

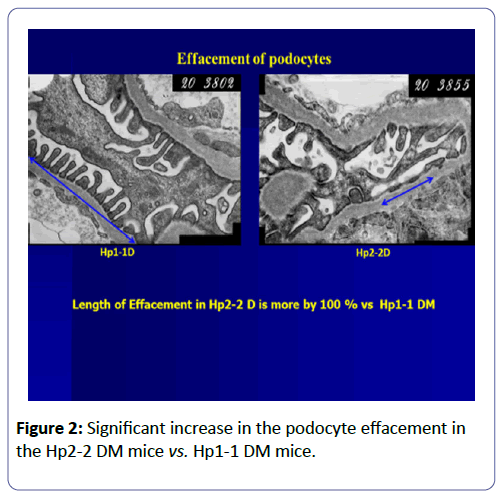

Podocytes play a role in early stages of diabetic glomerulopathy in patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus (T1DM and T2DM): Podocytes are very sensitive to the toxic effect of hyperglycaemia (glucose toxicity), and are primarily involved in diabetic nephropathy (Glomerular Theory) [6,7], with basement membrane thickening and mesangial matrix expansion with proteinuria due to podocyte effusion alterations in the structure of podocytes (Figure 1). The depletion of podocytes also plays an important role in the progression of diabetic nephropathy (DN). Podocytes are a critical part of glomerular filtration barrier terminally differentiated cells and generally do not replicate. Therefore, the intracellular degradation system may be important in maintaining podocyte homeostasis and integrity. At the same time, the proximal convolute tubular cells (PCT) [7-9] are also vulnerable to high glucose with increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) via increased deposition of iron in lysosomes (Proximal Tubular Theory).

Podocytes and PCT cells have evolved several mechanisms to face stress and to maintain cellular homeostasis, such as the anti-oxidative stress response and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response. Recently, the role of the autophagy-lysosome system in podocyte dysfunction under hyperglycaemic stress has been well-defined [10,11]. In addition, autophagy is an intracellular catabolic process in which proteins and organelles are degraded via lysosomes to maintain intracellular homeostasis under certain cytotoxic stress conditions in podocytes and proximal convolute tubules with hypertrophy and increased mitochondrial number [7]. Increased production of free radicals induces activation of both inflammatory and apoptotic signals. We published that haptoglobin (Hp) protein, with different genotypes, Hp1-1, Hp2-1, and Hp 2-2, is an important anti-oxidant in DM patients, especially those with Hp1-1. Increased deposition of iron in the PCT of diabetic mice with Hp2-2 was accompanied by increased production of free radicals compared with diabetic mice with Hp1-1 [9,12].

These findings allow us to hypothesize that hyperglycaemia/ diabetes can impair autophagic activity, making kidney cells, especially podocytes, vulnerable to diabetes-related metabolic stress (podocytopathy) [13-16]. Impaired autophagy may be involved in the pathogenesis of podocyte loss, leading to massive proteinuria with progression of DN to ESRD. Despite increased efforts to optimize renal and cardiovascular risk factors, such as hyperglycaemia, hypertension, obesity, and dyslipidaemia, they are often insufficiently controlled in clinical practice. Although current drug interventions mostly target a single risk factor, more substantial improvements of renal and cardiovascular outcomes can be expected when multiple factors are improved simultaneously. The effects of these drug classes include glomerular hypertension, renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS), glucose transporter 2 (SGL2), growth hormone, transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), advanced glycation products (AGEs), activation of protein kinase C (PKC), and different inflammatory and apoptotic signals. Also, the old antidiabetic agent metformin has pleiotropic actions that have been associated with the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). AMPK can be viewed indeed as a key that protects cells under energy-restricted conditions. It is activated by an increase in the AMP/ATP ratio and thus by an imbalance between ATP production and consumption. Thus autophagy can be considered as a new therapeutic target for diabetic nephropathy in the future [6,17,18].

Old Players: Renin-Angiotensin- Aldosterone System (RAAS)

The mechanisms behind the pathophysiology of DN are complex and continue to be not fully understood. Both metabolic (hyperglycaemia) and hemodynamic alterations interact synergistically, and have been reported to activate local RAAS resulting in increased angiotensin-2, reactive oxygen species (ROS), inflammation, expression of TGF-β, and dysregulation of different vascular growth factors such as the vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A).

Despite all of the beneficial interventions available for patients with diabetes, including tight glucose and blood pressure control, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition, and angiotensin II receptor or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism, renal disease remains prevalent and is likely to progress in most of these patients. Inhibition of the RAAS is the major focus of the current clinical therapy. However, agents that target the renin angiotensin system such as ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor-1 blockers (ARBs), have been only partially successful as these compounds just delay, rather than prevent, the progression to ESRD. Thus, there is an urgent need to identify better targets to prevent ESRD [17,18]. Additional treatment modalities that modulate the injurious pathways involved in diabetic nephropathy are therefore needed to slow the progression of renal disease in patients with diabetes. Still, the use of RAAS blockers as first-line blood pressure lowering agents in patients with DKD is based on high quality randomized controlled trials throughout the range of type 2 diabetes and diabetic kidney disease [19,20]. Despite the use of RAAS blockade in patients with diabetes mellitus, the data to support the efficacy of these agents is mainly in patients with significant proteinuria. Many physicians continue to treat all individuals with diabetes with a RAAS blocker. This practice is no longer mandated by the American Diabetes Association. These data indicate that an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) is not helpful in preventing progression of diabetic nephropathy in patients who are normotensive and normoalbuminuric. Multiple studies have demonstrated that for patients with diabetic nephropathy and more than 300 mg/day of proteinuria, treatment with RAAS blocking agents can slow progression to ESRD. Nevertheless, many patients continue to progress to ESRD despite being treated with maximally tolerated RAAS blockade. Furthermore, many patients cannot use RAAS blockers because of development of hyperkalaemia, particularly when the eGFR is <30 mL/min/1.73 m2. The efficacy of aldosterone blockers for slowing diabetic nephropathy progression has been less well studied, but these agents might be useful in combination with ACEI or ARB. Despite their limitations, RAAS blockers remain an important component of treatment in patients with advanced diabetic nephropathy. The newer potassium binding compounds could be added to RAAS blockade therapy for patients with advanced CKD. This would potentially permit continued use of RAAS inhibitors, despite reduced kidney function, in an effort to slow further CKD progression [18-20].

New Players: Autophagy

With recent intensive investigations, autophagy hopefully will be a potential therapeutic target to prevent or alleviate diabetic nephropathy (DN) [20]. Autophagy is the process responsible for recycling organelles and long-lived proteins to maintain cellular homeostasis. Autophagy can be stimulated during cellular stress to increase energy demands or to remove toxic protein aggregates and impaired organelles by intracellular mechanisms delivering cytoplasmic substrates to lysosomes for degradation by forming autophagosomes. There are two major subtypes of autophagy: macroautophagy, microautophagy. Macroautophagy refers to the process by which cytoplasmic constituents or organelles are sequestered in a double-membraned organelle called the autophagosome that fuses with a lysosome, facilitating their lysis. Of the three mechanisms, macroautophagy is the most predominant and complicated intracellular process and is often simply referred to as autophagy. Autophagy initiates with the formation of autophagophores, and the Beclin1-interacting complex that consists of Beclin1 and BCL-2 family proteins is required for the initiation process [21-23]. Autophagophores elongate and expand, and the elongation requires two ubiquitin-like conjugation systems: the ATG5-ATG12 conjugation system and the microtubule-associated protein light chain 3 (LC3/ATG8) conjugation system. The conversion of a cytosolic truncated form of LC3 (LC3-I) to the phosphatidylethanolamine-conjugated form (LC3-II) indicates autophagosome formation. Hyperglycaemia is thought to promote oxidative stress during diabetic complications such as DN in podocytes and PCT cells. Oxidative stress can be directly toxic to cells, causing damage to DNA, proteins, and lipids. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced from several sources in DN, with mitochondria considered one of the major sites [11,15,24,25].

Studies from animal models indicate that disturbances in mitochondrial homeostasis are central to the pathogenesis of DN. Since renal proximal tubule cells rely on oxidative phosphorylation to provide adequate ATP for tubular reabsorption, an impairment of mitochondrial function can result in renal function decline. Defects at the level of the electron transport chain have long been established in DN, promoting the formation of superoxide radicals, mediating inflammation, and contributing to the renal damage. Recent studies suggest that mitochondrial-associated proteins may be directly involved in the pathogenesis of tubulointerstitial fibrosis and glomerulosclerosis. The process of mitophagy is the selective targeting of damaged mitochondria by autophagosomes for degradation through the autophagy pathway. An impairment in the mitophagy system leads to the accelerated progression of renal pathology. A better understanding of the cellular and molecular events that govern mitophagy in DN may lead to improved therapeutic strategies in the future [11].

Altered mitochondrial morphology was first demonstrated in the proximal tubule cells of patients with type 2 diabetes and albuminuria. Renal biopsy specimens showed enlarged mitochondria with cellular hypertrophy and thickening of the tubular basement membrane. Our and other research groups showed that enlarged mitochondria in proximal tubule cells correlated with microalbuminuria in early diabetes in a rat and mouse model of streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetes (Figure 2).

In summary, in the kidneys, autophagy has been observed in proximal tubules, thick ascending limbs, and particularly in podocytes, which have a relatively high level of autophagy even under basal conditions. This indicates that autophagy is crucial for maintaining the function and homeostasis of podocytes. In renal proximal tubule cells, autophagy protects against high glucose-induced cell injury [11,15,26].

Klotho-Vitamin D-VDR Axis

Klotho as a negative regulator of intra-renal RAAS

α-Klotho is a multifunctional protein highly expressed in the kidney. Soluble αKlotho is released through cleavage of the extracellular domain from membrane αKlotho by secretases to function as an endocrine/paracrine substance [26-29]. Klotho is a trans-membrane protein that serves as the cofactor for fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF-23) to bind to its cognate receptor and regulate phosphorus and vitamin D metabolism. The soluble form of Klotho is reported to have anti-aging properties, which may be mediated via multiple systemic effects including regulation of insulin signalling and prevention of vascular calcium deposits, oxidative stress, and fibrosis. The kidney has the highest levels of Klotho expression and is thought to be the major source of soluble Klotho, which is released through proteolytic cleavage of the transmembrane form as well as alternative gene transcription.

Increasing evidence demonstrates that the renoprotective action of Klotho is through inhibition of intrarenal RAS. It has further been shown that Klotho may inhibit intrarenal RAS by targeting the Wnt/b-catenin signaling system. Klotho directly binds multiple Wnts, including Wnt1, Wnt4, and Wnt7a. Others have shown that Klotho exerted a direct inhibitory effect on aldosterone synthesis in adrenal glands. It is likely that Klotho may exert a multitude of actions to mitigate the activation of intrarenal RAS as well as systemic aldosterone production. Overall, strong evidence demonstrates the suppression of renal Klotho expression in diabetic renal disease, and more vigorous functional studies are needed to define the renoprotective action of this antiaging protein as well as its relationship with intrarenal RAS [30-35].

The Klotho protein also has endogenous anti-fibrotic function via antagonism of Wnt/β-catenin signalling, which promotes fibrogenesis, suggesting that loss of Klotho may contribute to the progression of DN by accelerated fibrogenesis. In addition to the effect of Klotho on Transforming Growth Factor β (TGF-β), suppressive effects of Klotho on the insulin-like growth factor pathway may be associated with inhibitory action on renal fibrosis [33-35] and cardio-renal protection in high oxidative stress conditions such as diabetes and its complications.

It is generally accepted that Klotho expression in the kidney is markedly decreased in the early stages of DN and in patients with CKD. Although the exact mechanism of how Klotho is reduced in diabetic kidney disease is not well understood, the increased oxidative stress, Ag-II, and TGFβ-1 may be involved. The hyperglycemic state is accompanied by increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by the Fenton reaction and consequently decreased Klotho [36-38].

Renal Klotho expression levels were decreased in patients with early DN and in the STZ-induced mouse model of T1DM. Recent work has shown that plasma and urine levels of soluble Klotho are significantly elevated in DM patients with relatively preserved renal function compared to control subjects. Hence, in DN, Klotho expression levels were decreased in kidneys of patients with early DN but with increased levels of plasma and urinary Klotho, and that Klotho deficiency may serve as a biomarker as well as a pathogenic factor for the progression of renal disease and further complications [39-41].

In vivo studies have shown that there is a therapeutic potential Klotho in several kidney disease models including DN in a mouse model. Klotho administration has been proven successful in the protection of kidney function in high glucose-induced glomerular damage. Although exogenous Klotho attenuates renal fibrosis, it is not known if exogenous Klotho attenuates diabetic nephropathy (DN).

Vitamin D/VDR

Nuclear receptors are found to be the negative regulators of inflammation, oxidative stress, and fibrosis. Vitamin D receptor (VDR) is one such nuclear receptor involved in various inflammatory pathways. Accurate identification of VDR in tissues is critical to understanding the physiopathological significance of vitamin D and could be key to the development of novel therapeutic modalities targeting the receptor. VDR is a transcription factor and intracellular receptor for 1-α,25- dihydroxyvitamin D3. VDR has been found in proximal and distal tubular epithelium, podocytes, and juxtaglomerular apparatus. Experimental studies have shown that VDR knockout mice have higher expression of renin, angiotensin, and angiotensin receptors under diabetic conditions and may develop severe renal injury resulting in early onset albuminuria, glomerulosclerosis, and interstitial fibrosis mainly due to local RAAS activation. Vitamin D exerts anti-inflammatory effects by modulating antigen-presenting cells’ function, reducing expression of cytokine interleukin-12 (IL-12), and repressing transcription of genes encoding interleukin 2 (IL2) and interferon gamma [42-44].

VDR is a well-established negative regulator of the RAS. Multiple clinical studies revealed an inverse relationship between plasma 1,25-(OH)2D3 concentrations and plasma renin activity in hypertensive patients as well as in normal subjects. At the cellular level, VDR directly suppresses renin gene transcription by interfering with cAMP responsive elements in the renin gene promoter. These results seem to suggest that VDR may primarily target the local RAS to confer cardiovascular and renal protection, especially in diabetic nephropathy [45-49].

The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) found an increase in the prevalence of albuminuria with decreasing 25(OH)D concentration. Vitamin D and its analogues have been used in patients with CKD with considerable improvement in kidney functions, in terms of reduced urinary albumin creatinine ratio and improved eGFR. Numerous observational studies showed multiple beneficial effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 or vitamin D analog therapy (paricalcitol) in patients with kidney disease, especially DN, that led to a significant survival advantage for patients receiving the therapy. A key renoprotective function of vitamin D is reduction of albuminuria or proteinuria, major risk factors for CKD progression, renal failure, cardiovascular events, and death. This anti-proteinuric effect and slowing the progression of DN is mediated primarily via the RAAS [50-53]. Wang and his group from the University of Chicago used the 2.5-kb human podocin gene promoter to target Flag-tagged human VDR (hVDR) to podocytes in DBA/2J mice, a genetic background known to be susceptible to diabetic renal injury. This podocin gene promoter has been well-documented for its podocyte specificity in driving transgene expression. To test whether an increase in podocyte VDR would enhance the renoprotective effect of vitamin D, they compared the therapeutic efficacy of a low dose vitamin D analog, doxercalciferol, between STZ-induced diabetic wild-type (WT) and hVDR transgenic (Tg) mice. Thus, podocyte VDR overexpression renders the mice more sensitive to vitamin D therapy. In fact, TG mice showed significantly reduced albuminuria compared with WT mice even at baseline. Thus, they provide mechanistic insights into the ever-increasing epidemiologic and clinical evidence linking vitamin D deficiency to renal and cardiovascular problems, and provide a molecular basis to explore therapeutic use of vitamin D and its analogs in the prevention and intervention of these diseases [54-56].

The synergistic therapeutic effects of combined vitamin D analog paricalcitol (19-0nor-1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D2) with AT1 receptor antagonist (Losartan) on kidney disease in a model of type 2 diabetic mice showed a dramatic therapeutic synergism, manifested by prevention of progressive albuminuria, restoration of the glomerular filtration barrier, reversal of the decline in slit diaphragm proteins, and reduction of glomerulosclerosis [56].

More, a primary increase in 1,25-(OH)2D3 up-regulates Klotho expression, which in turn suppresses 1,25-(OH)2D3 production, and likewise an increase in Klotho will suppress 1,25-(OH)2D3 to remove a major stimulator of Klotho production, Renal 1α- hydroxylase, resulting in a decreased conversion of 25- hydroxyvitamin D to 1,25-(OH)2D3. FGF-23 also regulates renal 1,25-(OH)2D3 levels by inducing expression of the catabolic enzyme 24-hydroxylase. These functions of FGF-23 are dependent on the presence of the transmembrane Klotho.

Sodium-Glucose-Co transporter (SGL2) blockers

There is increasing evidence that renal proximal tubular glucose absorption is increased in human and animal models of diabetes mellitus. Renal proximal tubular glucose transport is mediated by sodium glucose transporters SGLT2 and SGLT1, located on the apical membrane of the early and late segments of the proximal tubule, respectively [57].

The increased risk for microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes (T2D), including diabetic nephropathy (DN), cannot be explained by chronic hyperglycemia alone but involves other risk factors, such as obesity, arterial hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. Despite intensified pharmacologic interventions (e.g., antihyperglycemic agents, statins, and blood pressure lowering such as renin-angiotensin system [RAS] blockers) to strictly control these risk factors, the prevalence of diabetic nephropathy continues to rise and has become the leading cause for ESRD worldwide [58]. Moreover, DN is strongly associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and increased 10- year mortality from 12% in patients with T2D without DN to 31% in patients with DN.

The recently introduced selective sodium-glucose cotransporter type 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors improve glycemic control by blocking glucose reabsorption in the renal proximal tubule, thereby enhancing urinary glucose excretion. SGLT2 inhibitors exert multiple beneficial effects, including reductions in body weight and serum uric acid, as well as BP lowering and attenuation of glomerular hyperfiltration, which are likely, linked to glycosuria-accompanied natriuresis, presumably by stimulating the tubulo-glomerular feedback (TGF) mechanism. Collectively, these actions beyond glucose lowering may help to explain the observed renal and cardiovascular benefits of the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin in the large-sized randomized, placebo-controlled, cardiovascular clinical trial (EMPA-REG OUTCOME). After a median of 3.1 years of follow-up, not only was empagliflozin use linked to fewer cardiovascular and death events but it also improved kidney-related outcomes. Specifically, it was associated with a statistically significant lower incidence rate of macroalbuminuria (38%), doubling of serum creatinine and eGFR# 45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (44%), and initiation of dialysis (55%). In addition, as we mentioned above, the sodium glucose transport type 2 inhibitor also can ameliorate the autophagy process that is down regulated in the proximal tubular cells due to hyperglycemia [57-61].

Discussion

DN is one of the major complications of diabetes and is characterized by metabolic disorders, albuminuria, and decreased glomerular filtration rate. Although the molecular mechanisms are not fully understood, activation of the renin angiotensin aldosterone pathway is one of many other pathways involved. In spite of a combination of different treatments in DM patients, the number of dialysis patients is increasing yearly. Recently other pathways have been found to be involved, such as increased production of reactive oxygen species, TGF-β, the vitamin D-VDR Klotho axis, and autophagy. The autophagy process has been known to play a role in maintaining cellular homeostasis and energy balance [11,25]. Therefore, the regulation of autophagy is thought to be a major therapeutic target for DN.

Studies were performed using different treatments for autophagy repair. Recent studies have shown that mTORC1 signalling is highly activated in podocytes of diabetic kidneys in humans and animals. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a protein kinase that is broadly expressed in multiple organs and cells, including podocytes and proximal convolute tubule cells. mTOR signalling is vital in body energy metabolism, regulating cell proliferation. Rapamycin inhibits mTOR activity, and different studies have shown that rapamycin supplementation can suppress vascular inflammation and fibrosis.

The role of rapamycin, an mTORC1 blocker, in mice with DN, was studied by different researchers with positive results. It has been reported that reabsorption of albuminuria elicits autophagy in the proximal tubular epithelium as a renoprotective process, and proteinuria-induced autophagy was suppressed via hyper-activation of mTORC1 under hyperglycaemic conditions. Previous studies have showed that rapamycin treatment can ameliorate renal hypotrophy in a mouse model of diabetes via inhibition of mTORC1 [11,15,23-25]. In addition, mTOR signaling inhibition might be associated with renal function reserve in chronic diabetic kidney disease (CDKD). More data is available now on the cross talk between Klotho and mTORC1 in the hyperglycemic state, where Klotho expression is decreased in early stages of DN. Rapamycin upregulates Klotho in renal tubular epithelial cells, where studies have shown that rapamycin induced Klotho expression by activating the mTORC2 pathway [63,64].

Another player in the pathogenesis and treatment of DN is Aldosterone. In the podocyte, aldosterone plays a pathogenic role in renal injury under conditions of DN, and aldosterone-treated mouse podocytes showed significantly increased conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II, Beclin1 expression, indicating altered autophagy status with subsequent renal injury.

Despite the intensified multifactorial treatment in T2D, traditional risk factors are usually inadequately controlled in daily practice, and DKD as well as CVD remain common complications that have a major effect on global health care. SGLT2 inhibitors are novel anti-hyperglycaemic drugs that effectively reduce glucose by stimulating urinary glucose excretion, while simultaneously improving multiple other risk factors in a glucose-independent manner. Collectively, these effects resulted in a remarkable improvement of renal and cardiovascular outcomes. Moshe Levy et al. [57] showed, in agreement with other studies, in both insulin deficient and insulin intact db/db animals, that SGLT2 inhibition results in a decrease in proteinuria and inflammation in the kidney. In addition, they showed that these beneficial effects are associated with significant decreases in mesangial expansion, accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins, fibrillary collagens, and prevention of podocyte loss, which are the hallmarks of diabetic nephropathy [62].

Different studies have shown that SGLT2 inhibitors, empagliflozin and dapagliflozin, ameliorated diabetic nephropathy by attenuating albuminuria, mesangial expansion and interstitial fibrosis via combined effects on glomerular hemo-dynamics and inhibition of renal inflammation and oxidative stress mostly secondary to improvement of glycemia. These in vivo findings confirmed previous in vitro evidence that SGLT2 inhibitors attenuated inflammatory and fibrotic responses of proximal tubular epithelial cells exposed to high glucose.

Among the new anti-diabetic medications that target a specific pathophysiologic pathway, the SGLT2 inhibitors are of major future interest in the treatment of early stage DN. Since SGLT2 inhibitors act via a different mechanism than other oral anti-hyperglycemic drugs, they can be first line treatment in T2DM and DN in the future [62,65].

References

- Doshi SM, Friedman AN (2017) Diagnosis and Management of Type 2 Diabetic Kidney Disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol.

- Montero RM, Covic A, Gnudi L, Goldsmith D (2016) Diabetic nephropathy: What does the future hold? Int Urol Nephrol 48: 99-113.

- Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Shaw J (2001) Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature 414: 782-787.

- Alicic Z, Rooney MT, Tuttle Radica KR (2017) Diabetic Kidney Disease: Challenges, Progress, and Possibilities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJN.11491116.

- Bhattacharjee N, Barma S, Konwar N, Dewanjee S,Manna P (2016) Mechanistic insight of diabetic nephropathy and its. Pharmacotherapeutic targets: An update.Eur J Pharmacol 791: 8-24.

- Campbell KN, Raij L, Mundel P (2011) Role of angiotensin II in the development of nephropathy and podocytopathy of diabetes. Curr Diabetes Rev 7: 3-7.

- Asleh R, Nakhoul FM, Miller-Lotan R, Awad H, Farbstein D, et al. (2012) Poor lysosomal membrane integrity in proximal tubule cells of haptoglobin 2-2 genotype mice with diabetes mellitus. Free Radic Biol Med 53:779-786.

- Park JH, Jang HR, Lee JH, Lee JE, Huh W, et al. (2015) Comparison of intrarenal renin-angiotensin system activity in diabetic versus non-diabetic patients with overt proteinuria. Nephrology (Carlton) 20: 279-285.

- Levy AP (2004) Haptoglobin: a major susceptibility gene for diabetic cardiovascular disease. Isr Med Assoc J 6: 308-310.

- Yasuda-Yamahara M, Kume S, Tagawa A, Maegawa H, Uzu T (2015) Emerging role of podocyte autophagy in the progression of diabetic nephropathy. Autophagy 11: 2385-2386.

- Xin W, Li Z, Xu Y, Yu Y, Zhou Q, et al. (2016) Autophagy protects human podocytes from high glucose-induced injury by preventing insulin resistance. Metabolism 65: 1307-1315.

- Nakhoul FM, Miller-Lotan R, Awad H, Asleh R, Jad K, et al. (2009) Pharmacogenomic effect of vitamin E on kidney structure and function in transgenic mice with the haptoglobin 2-2 genotype and diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F830-F838.

- Hayashi K, Ohashi H, Ugi S, Maegawa H, Uzu T (2016) Impaired Podocyte Autophagy Exacerbates Proteinuria in Diabetic Nephropathy. Diabetes 65: 755-767.

- Tagawa A, Yasuda M, Kume S, Yamahara K, Nakazawa J, et al. (2013) Mechanisms of Disease. Review article. Autophagy in Human Health and Disease. N Engl J Med 368: 651-662.

- Leventhal JS, Wyatt CM, Ross MJ (2017) Translational science Recycling to discover something new: the role of autophagy in kidney disease. Kidney Int 91: 4-6.

- Yacooub R, Cambell KN (2015) Inhibition of RAS in diabetic nephropathy. Int J Nephrol Renovascular Dis 8: 29-40.

- Majewski C, Bakris GL (2016) Has RAAS Blockade Reached Its Limits in the Treatment of Diabetic Nephropathy? Review Curr Diab Rep 16: 24.

- Ruggenenti P, Cravedi P, Remuzzi (2010) The RAAS in the pathogenesis and treatment of diabetic nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol 6: 319-330.

- Ilyas Z, Chaiban JT, Krikorian A (2017) Novel insights into the pathophysiology and clinical aspects of diabetic nephropathy. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 18: 21-28.

- Su J, Zhou L, Kong X, Yang X, Xiang X, et al. (2013) Endoplasmic Reticulum Is at the Crossroads of Autophagy, Inflammation, and Apoptosis Signaling Pathways and Participates in the Pathogenesis of Diabetes Mellitus. J Diabetes Res 2013.

- Higgins GC, Coughlan MR (2014) Review: Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitophagy: the beginning and end to diabetic nephropathy? Br J Pharmacol 171: 1917-1942.

- Ding Y, Choi ME (2015) Autophagy in diabetic nephropathy. J Endocrinol 224: R15-R30.

- Wang Z, Choi ME (2014) Autophagy in kidney health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 20: 519-537.

- Liu N, Xu L, Shi Y, Zhuang S (2017) Podocyte Autophagy: A Potential Therapeutic Target to Prevent the Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy. J Diabetes Res 2017.

- Hu MC, Kuro-o M, Moe OW (2013) Renal and extrarenal actions of Klotho. Semin Nephrol 33: 118-129.

- Dërmaku-Sopjani M, Kolgeci S, Abazi S, Sopjani M (2013) Significance of the anti-aging protein Klotho. Mol Membr Biol 30: 369-385.

- Schmid C, Neidert MC, Tschopp O, Sze L, Bernays RL (2013) Growth hormone and Klotho. J Endocrinol 219: R37-57.

- Xu Y, Sun Z (2015) Molecular basis of Klotho: from gene to function in aging. Endocr Rev 36: 174-193.

- Lindberg K, Amin R, Moe OW, Hu MC, Erben RG, et al. (2014) The kidney is the principal organ mediating klotho effects. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 2169-2175.

- Hu MC, Kuro-o M, Moe OW (2012) The emerging role of Klotho in clinical nephrology. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 2650-2657.

- Drew DA, Katz R, Kritchevsky S, Ix J, Shlipak M, et al. (2017) Association between Soluble Klotho and Change in Kidney Function: The Health Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 1859-1866.

- Kacso IM, Bondor CI, Kacso G (2012) Soluble serum Klotho in diabetic nephropathy: relationship to VEGF-A. Clin Biochem 45: 1415-1420.

- Mitobe M, Yoshida T, Sugiura H, Shirota S, Tsuchiya K, et al. (2005) Oxidative stress decreases klotho expression in a mouse kidney cell line. Nephron Exp Nephrol 101: e67-e74.

- Lee EY, Kim SS, Lee JS, Kim IJ, Song SH, et al. (2014) Soluble α-klotho as a novel biomarker in the early stage of nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. PLoS One 9: e102984.

- Zhao Y, Banerjee S, Dey N, LeJeune WS, Sarkar PS, et al. (2011) Klotho depletion contributes to increased inflammation in kidney of the db/db mouse model of diabetes via RelA (serine) 536 phosphorylation. Diabetes 60: 1907-1916.

- Asai O, Nakatani K, Tanaka T, Sakan H, Imura A, et al. (2012) Decreased renal α-Klotho expression in early diabetic nephropathy in humans and mice and its possible role in urinary calcium excretion. Kidney Int 81: 539-547.

- Cheng MF, Chen LJ, Cheng JT (2010) Decrease of Klotho in the kidney of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010: 513853.

- Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Clark JD, Pastor JV, Nandi A, et al. Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho. Science 309: 1829-1833.

- Lin Y, Kuro-o M, Sun Z (2013) Genetic deficiency of anti-aging gene klotho exacerbates early nephropathy in STZ-induced diabetes in male mice.Endocrinology 154: 3855-3863.

- Haruna Y, Kashihara N, Satoh M, Tomita N, Namikoshi T, et al. (2007) Amelioration of progressive renal injury by genetic manipulation of Klotho gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 2331-2336.

- Li YC (2010) Renoprotective effects of vitamin D analogs. Kidney Int 78: 134-139.

- Tangpricha V, Judd SE, Kamen D, Li YC, Malabanan A (2010) Vitamin d. Int J Endocrinol 2010: 631052.

- Haussler MR, Whitfield GK, Kaneko I, Haussler CA, Hsieh D, et al. (2013) Molecular mechanisms of vitamin D action. Calcif Tissue Int 92: 77-98.

- Zhang Y, Deb DK, Kong J, Ning G, Wang Y, et al. (2009) Long-term therapeutic effect of vitamin D analog doxercalciferol on diabetic nephropathy: strong synergism with AT1 receptor antagonist. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F791-F801.

- Li YC, Kong J, Wei M, Chen ZF, Liu SQ, et al. (2002) 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) is a negative endocrine regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. J Clin Invest 110: 229-238.

- Peng Y, Li LJ (2015) Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level and diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int Urol Nephrol 47: 983-989.

- Li YC (2003) Vitamin D regulation of the renin-angiotensin system. J Cell Biochem 88: 327-331.

- Li YC (2014) Discovery of vitamin D hormone as a negative regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. Clin Chem 60: 561-562.

- Li YC (2013) Vitamin D receptor signaling in renal and cardiovascular protection. Semin Nephrol 33: 433-447.

- Tian Y, Lv G, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Yu R, et al. (2014) Effects of vitamin D on renal fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy model rats. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 7: 3028-3037.

- Al-Badr W, Martin KJ (2008) Vitamin D and kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1555-1560.

- Gysemans C, van Etten E, Overbergh L, Giulietti A, Eelen G, et al. (2008) Unaltered diabetes presentation in NOD mice lacking the vitamin D receptor. Diabetes 57: 269-275.

- Li YC (2011) Podocytes as target of vitamin D. Curr Diabetes Rev 7: 35-40.

- Dusso AS (2012) Renal vitamin D receptor expression and vitamin D renoprotection. Kidney Int 81: 937-939.

- Wang Y, Deb DK, Zhang Z, Sun T, Liu W, et al. (2012) Vitamin D receptor signaling in podocytes protects against diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1977-1986.

- Deb DK, Sun T, Wong KE, Zhang Z, Ning G, et al. (2010) Combined vitamin D analog and AT1 receptor antagonist synergistically block the development of kidney disease in a model of type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int 77: 1000-1009.

- Wang XX, Levi J, Luo Y, Myakala K, Herman-Edelstein M, et al. (2017) SGLT2 Expression is increased in Human Diabetic Nephropathy: SGLT2 Inhibition Decreases Renal Lipid Accumulation, Inflammation and the Development of Nephropathy in Diabetic Mice. J Biol Chem 292: 5335-5348.

- Bhattacharjee N, Barma S, Konwar N, Dewanjee S, Manna P (2016) Mechanistic insight of diabetic nephropathy and its pharmacotherapeutic targets: An update. Eur J Pharmacol 791: 8-24.

- Davies MJ, Merton KW, Vijapurkar U, Balis DA, Desai M (2017) Canagliflozin improves risk factors of metabolic syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 10: 47-55.

- van Bommel EJM, Muskiet MHA, Tonneijck L, Kramer MHH, Nieuwdorp M, et al. (2017) SGLT2 Inhibition in the Diabetic Kidney—From Mechanisms to Clinical Outcome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 700-710.

- Chokhandre MK, Mahmoud M, Hakami T, Jafer M, Inamdar AS (2015) Vitamin D & its analogues in type 2 diabetic nephropathy: a systematic review. J Diabetes Metab Disord 14: 58.

- Declèves AE, Sharma K (2014) Novel targets of antifibrotic and antiinflammatory treatment in CKD. Nat Rev Nephrol 10: 257-267.

- Yang Z, Ming-Ming Z, Yan C, Ming-Fei Z, Wei-Liang S, et al. (2015) Mammalian target of rapamycin signaling inhibition ameliorates vascular calcification via Klotho upregulationl. Kidney international 88: 711-721.

- Ying X, Lei L, Wei X, Xu Z, Liyong C, et al. (2015) The renoprotective role of autophagy activation in proximal tubular epithelial cells in diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Complications 29: 976-983.

- Kuecker CM, Vivian EM (2016) Patient considerations in type 2 diabetes–role of combination dapagliflozin–metformin XR. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 9: 25-35.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences