Basics of Medical Documentation for Nephrologists Practicing in the United States

Elvira O Gosmanova, Aidar R Gosmanov and Robert B Canada

DOI10.21767/2472-5056.100005

Elvira O Gosmanova1*, Aidar R Gosmanov2 and Robert B Canada1

1 Renal Section, Stratton VA Medical Center, Albany, NY

2 Endocrinology Section, Stratton VA Medical Center, Albany, NY

3 Nephrology Division, Department of Medicine, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN

- *Corresponding Author:

- Elvira O Gosmanova

MD, FASN, Nephrology Section, Samuel S. Stratton VA Medical Center

113 Holland Ave, Albany, NY 12211

Tel: (518)-626-6463,

E-mail: elvira.gosmanova@va.gov

Received date: November 18, 2015, Accepted date: December 21, 2015, Published date: December 25, 2015

Citation: Gosmanova EO, Gosmanov AR, Canada RB (2016) Basics of Medical Documentation for Nephrologists Practicing in the United States. J Clin Exp Nephrol 1:5. DOI: 10.21767/2472-5056.100005

Copyright: © 2016 Gosmanova EO, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

As nephrologists we spend a considerable amount of time mastering the art of diagnosing and treating kidney diseases, which is paramount for improving health of our patients. However, it is equally important to have a solid understanding of basics of medical documentation and how it applies to a nephrology subspecialty in order to communicate with other providers and auditors, and receive appropriate reimbursement for rendered services. In addition, the knowledge of medical documentation helps to avoid over performing and documenting unnecessary findings, and allows to concentrate on a key elements supporting medical decision making, thereby, contributing to overall efficiency. This paper overviews the structure of medial documentation and its key sections such as History, Physical examination, and Medical decision making. We also review documentation requirements for different types and levels of medical encounters routinely performed by nephrologists, including documentation for dialysis encounters.

Keywords

Medical documentation; Medical encounter; Dialysis documentation

Introduction to Medical Documentation

Medical documentation is an essential part of medical practice and it evolved from its original didactic role of teaching interesting medical cases to a legal document that is the base of provider’s payment for rendered medical services [1]. No explicit guidelines exist about elements of medical documentation that could protect a provider during medical malpractice lawsuit. It is a general rule, that providers should document key clinical and diagnostic findings supporting assessment. During discussion with patients and documentation of assessment, it is advisable to avoid false certainties in diagnosis. It is appropriate to indicate in assessment that the final diagnosis is not reached and use terms “likely diagnosis” or “probable diagnosis”. This reduces unrealistic patient’s expectations and increases patient’s acceptance if changes in treatment plan become necessary [2]. In addition, it is prudent to include brief statement describing patient’s understanding of possible outcomes and patient’s agreement with proposed treatment plan [2]. On the other hand, when it comes to the medical billing, the Congress issued a very specific set of guidelines, which have to be followed in the medical documentation in order to qualify for the requested level of payment [3,4]. A provider can only bill for a medical service based on what is included into medical documentation with legal assumption that documented service was actually performed and based on the necessity and appropriateness for a particular patient [5]. Therefore, from the billing prospective, the medical documentation is a justification of medical service provided during medical encounter.

Evaluation and Management or E/M coding – is a system used by all providers in the US to receive reimbursement from all types of payers (government and private insurances) that was established by the Congress in 1995 and further updated in 1997 [3-5]. E/M coding is based on Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®, copyright by the American Medical Association (AMA)) codes for the medical services and uses diagnostic codes for the medical conditions from the International Classification of Diseases- Clinical Modification (ICD-CM) codes. Starting October 1, 2015, current ICD-CM 9th revision will be replaced by ICD CM 10th revision. ICD codes are used to support diagnosis and management during medical encounter; while, CPT® codes describe location, type and level of medical service.

Applicable to the nephrology subspecialty, the location of services is generally divided into outpatient (office) and inpatient (hospital). Initial evaluation, consultation, and subsequent evaluation are types of services. There are different levels of service exist within each type of evaluation due to patients’ heterogeneity and the complexities of presenting medical problems Table 1. Medicare and Medicaid recognize only initial inpatient visits (CPT® codes 99221-99223) and initial outpatient visits (CPT® codes 99201-99205). While, private insurances may also allow using consultation E/M codes for inpatient (CPT® codes 99251-99255) and outpatient (CPT® codes 99241- 99245) consultation services, which sometimes require less documentation and may have a slightly better reimbursement than corresponding initial evaluation CPT® codes. Many providers delegate the process of billing to designated coders; however, the accurateness of submitted billing is the provider’s responsibility, and, therefore, provider’s familiarity with patient’s insurance plan is important for appropriate coding. In general, the higher level of service within each encounter reflects increasing complexity of the patient and/or decisions/treatment options required for the patient, and corresponds to a higher reimbursement for the encounter [6].

| Inpatient (Hospital)CPT ®codes | Outpatient (Office)CPT ® codes | |

|---|---|---|

| Initial evaluation | First encounter during hospitalization (a patient can be new to a provider or previously seen by a provider or his/her partner in inpatient or outpatient setting) 99221-99223 (3 levels) |

First encounter and a patient was not previously seen by provider or his/her partner from the same group within 3 calendar years 99201-99205 (5 levels) |

| Subsequent evaluation (subsequent care) | 99231-99233 (3 levels) | 99211-99215 (5 levels) |

| Consultation* | First encounter during hospitalization (patient can be new to a provider or previously seen by a provider or his/her partner in inpatient or outpatient setting) 99251-99255 (5 levels) |

First encounter and a patient was not previously seen by provider or his/her partner from the same group within 3 calendar years 99241-99245 (5 levels) |

| Evaluation during dialysis | 90935- hemodialysis with single evaluation 90945- hemodialysis with multiple evaluations 90945- dialysis non-hemo with single evaluation 90946- dialysis non-hemo with multiple evaluations |

Hemodialysis: 90960 (4 face-to face monthly visits), 90961 (2-3), 90962 (1) Home dialysis therapies: 90966 |

Table 1 Types of medical encounters.

The most common types of medical documentation performed by nephrologists correspond to initial and subsequent inpatient and outpatient visits. We will also briefly review documentation for the time-based encounters and inpatient and outpatient dialysis documentation.

Structure of Medical Documentation

In order to qualify for the billing, E/M requirements for the most types of medical documentation include the presence of 3 key blocks/sections helping to convey the information about patient’s visit and what and why certain procedures or treatments were prescribed: (1) History, (2) Physical examination, and (3) Medical Decision Making [3,4]. Since the baseline complexity and the nature of presenting problems vary from patient to patient, different levels of service exist within each type of medical encounters. Below, we will review each 3 key sections and provide examples related to the nephrology specialty. It is important to note, that there are two-1995 [3] and 1997 [4] documentation guidelines for E/M services, which share significant similarities but also have differences. Although, it is a provider’s choice as to which set of guidelines to follow, both guidelines cannot be used in the same encounter documentation; i.e., if 1997 guidelines are followed for History block, the same guidelines should be followed for Physical examination. We will discuss application of both 1995 and 1997 guidelines for medical documentation of inpatient and outpatient initial and subsequent evaluation encounters. There are also different types of medical encounters where the 3 key elements of E/M may not play the predominant role and the time of service provision becomes a predominant factor determining level of service [7]. Examples of such encounters include patient counseling and coordination of care [8]. The complexity of encounter, which is turn, determined by presenting problem(s) and the type of encounter (initial or subsequent) dictates the amount of necessary documentation to qualify for an intended level of service.

History Block of Medical Documentation

History section consists of 4 parts: (1) chief complaint (CC) or reason for the visit (RFV), (2) history of present illness (HPI), (3) past medical, surgical, and social history (PFSH), and (4) review of systems (ROS). Here it gets complicated, because within each part of History, there are different levels of complexity Table 2. Levels of HPI, PFSH, and ROS are then combined to achieve the total level of History from a straightforward to a complex History [3,4,6].

| History(4 levels) | RFV/CC | HPI(2 levels) | ROS(4 levels) | PFSH(3 levels) | Examples of medical encounters (CPT® codes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem Focused | + | 1. Brief (1-3 HPI elements) |

None | None | Subsequent visit (99211, 99212, 99231) |

| Expanded Problem Focused | + | 1. Brief (1-3 HPI elements) |

1 organ system | None | Initial evaluation (99202) Subsequent visit (99213, 99232) |

| Detailed | + | 2. Extended (≥4 HPI elements or status of 3 chronic or inactive problems) |

2-9 organ systems | 1 out of 3 elements | Initial evaluation (99203, 99221, 99253) Subsequent visit (99214, 99233) |

| Comprehensive | + | 2. Extended (4 and >HPI elements or status of 3 chronic or inactive problems) |

≥10 organ systems | 3 out of 3 elements | Initial evaluation (99204, 99205, 99222, 99223, 99254, 99255) Subsequent visit (99215) |

Social History; CPT®: Current Procedural Terminology, copyright American Medial Association

Table 2 History block of medical documentation

Each medical encounter submitted for the billing irrespective of its level of service should have a reason for the visit (RFV) or chief complaint (CC). CC may not be elicited or present in all encounters (for example, intubated patient in ICU would not be able to provide CC, or stable patient coming for a routine followup visit may not have any complaints) and, therefore, RFV can be used as a substitute for CC. Examples of RVF for initial hospital evaluation or consultation, as well as subsequent visits, could be “Management of acute kidney injury (AKI)” or “Management of end-stage renal disease (ESRD)”. Examples of RFV for outpatient visit are “Follow-up of chronic kidney disease and hypertension” or “Follow-up of lupus nephritis”.

The HPI is a chronological description of present signs/symptoms from its onset or from the last encounter and includes the following 8 HPI elements such as location, severity, quality, duration, timing, context, modifying factors, and associated signs and symptoms [3,4]. There are 2 levels of HPI Table 2 brief and extended. The main difference between 1995 and 1997 guidelines for the History block is in definition of extended HPI. The 1995 guidelines define extended HPI as documentation of 4 or more HPI elements. However, this approach limits the ability to describe outpatient encounters when patient may have several serious medical problems but in stable condition, thus, not allowing to gather 4 elements of HPI in absence of new symptoms. Therefore, the 1997 E/M guidelines also included into the definition of extended HPI “the status of 3 or more chronic or inactive medical conditions”.

A ROS is an inventory of 14 body systems (constitutional, eyes, ear/ nose/mouth/throat, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, musculoskeletal, integumentary (skin/breast), neurologic, psychiatric, endocrine, hematologic/lymphatic, allergic/immunologic) that is designed to obtain information about all possible symptoms patient may experience. The main purpose of ROS is to get comprehensive information about patient’s symptoms to better understand the presenting complaint but also to elicit concomitant conditions. Comprehensive ROS with at least 10 organ systems reviewed is required during all initial encounters; however, more limited ROS can be sufficient for other patient’s visits Table 2. For comprehensive ROS it is acceptable to list all pertinent positive and negative symptoms and document (after performing it) that all other systems were reviewed and were negative.

A PFSH block consists of 3 areas: (1) past history, (2) family history (pertinent to the presenting problem), and (3) social history. Each area can have multiple items, as for example, past history can include previous illnesses, surgical history, current medications, or social history can include smoking or alcohol consumption, marital status, occupation, etc. However, only one item from each PFSH area is required to satisfy E/M requirements for comprehensive PFSH Table 2. One element from any of 3 PFSH areas should be included into pertinent PFSH.

The HPI is the only part of History, which has to be personally obtained and documented by the provider. Both ROS and PFSH can be documented by a medical assistant or obtained from patient questionnaires; however, that information should be readily available in the medical chart, and reviewed and acknowledged in the medical documentation by the provider. The overall level of History is determined by the individuals levels if History elements (HPI, ROS, and PFSH) and summarized in Table 2.

Physical Examination Block of Medical Documentation

The understanding of Physical examination block of medical documentation could be a confusing part of E/M requirements. Although, the 1995 and 1997 E/M guidelines share similarity in definition concerning physical examination requirements for each level of Physical Examination, it may be easier to understand the 1997 guidelines given more defined (numerical) description of what should be included into medical documentation for any given level of service Table 3. Nevertheless, the 1995 guidelines work well when less detailed physical examination is sufficient. Both, the 1995 and 1997 guidelines for the physical examination recommend describing alone or in combination (depending on a level of service) of 7 body areas (head/ face, neck, chest/breast/axilla, abdomen, genitalia/buttocks/ groin, back/spine, each extremity) and 12 organ systems (constitutional, eyes, ear/nose/mouth/throat, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, musculoskeletal, skin, neurologic, psychiatric, hematologic/lymphatic/immunologic) during physical examination. In contrast to the 1995 guidelines, the 1997 guidelines provide specific examples of bullets (with corresponding elements) for each body area and organ system. We refer readers to the original CMS document for the detailed description of specific bullets (overall >50); however, examples of some of the most commonly used physical exam bullets related to nephrology specialty are listed in Table 4. The main difference between the 1995 and 1997 guidelines is the best illustrated for the comprehensive physical examination, when description of 8 body areas or organ systems is recommended in the 1995 guidelines, and total 18 bullets from at least 9 body areas/organ systems in the 1997 guidelines (at least 2 bullets from each 9 areas/systems).

| Physical examination(4 levels) | 1995 E/M guidelines | 1997 E/M guidelines | Examples of medical encounters(CPT® codes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Problem Focused | A limited examination of affected body area or organ system | 1-5 bullets from ≥1 body area(s) or organ system(s) | Initial evaluation (99201) Subsequent visit (99212, 99231) |

| Expanded Problem Focused | A limited examination of the affected body area or organ system and other symptomatic or related organ system(s) |

At least 6 bullets from ≥1 body area(s) or organ system(s) | Initial evaluation (99202) Subsequent visit (99213, 99232) |

| Detailed | An extended examination of the affected body area(s) and other symptomatic or related organ system(s) | At least 2 bullets from 6 body areas/systems or 12 bullets from ≥2 body area(s) or organ system(s) |

Initial evaluation (99203, 99221, 99253) Subsequent visit (99214, 99233) |

| Comprehensive | A general multi-system examination or complete examination of a single organ system. Findings from ≥8 organ systems | At least 2 bullets from 9 body areas/systems | Initial evaluation (99204, 99205, 99222, 99223, 99254, 99255) Subsequent visit (99215) |

Table 3 Physical examination block of medical documentation.

| Organ System/Body Area | Examples of elements included into bullet | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | 1)List any 3 out of 7 vital signs (sitting or standing blood pressure, supine blood pressure, heart rate and regularity, respiratory rate, temperature, height, weight) 2)General appearance of patient |

|||

| Ears, nose, mouth, and throat | 1) Inspection of conjunctivae and lids 2) Examination of pupils and irises (e.g., reaction to light and accommodation, size and symmetry) |

|||

| Neck | 1) Examination of neck (e.g., masses, overall appearance, symmetry, tracheal position, crepitus) 2) Examination of thyroid (e.g., enlargement, tenderness, mass) |

|||

| Respiratory | 1)Assessment of respiratory effort 2)Percussion of chest 3)Palpation of chest 4)Auscultation of lungs |

|||

| Cardiovascular | 1)Palpation of heart 2) Auscultation of heart 3) Examination of any of the following arteries: carotid arteries, abdominal aorta, femoral arteries 4) Examination of pedal pulses 5) Examination of extremities for edema and/or varicosities 6) Examination of arteriovenous fistula or graft is also included |

|||

| Gastrointestinal (Abdomen) | 1)Examination of abdomen 2)Examination of liver and spleen 3)Examination for presence or absence of hernia |

|||

| Musculoskeletal | 1) Examination of gait and station 2) Inspection and/or palpation of digits and nails (e.g., clubbing, cyanosis, inflammatory conditions, petechiae, ischemia, infections) 3) Assessment of muscle strength and tone (e.g., flaccid, cog wheel, spastic) with notation of any atrophy or abnormal movements |

|||

| Skin | 1) Inspection of skin and subcutaneous tissue (e.g., rashes, lesions, ulcers) 2) Palpation of skin and subcutaneous tissue (e.g., induration, subcutaneous nodules, tightening) |

|||

| Psychiatric | 1) Description of patient’sjudgment and insight 2) Assessment of orientation to person, place, and time |

|||

| Neurologic | 1)Examination of asterexis 2)Examination of sensation |

|||

Table 4 Examples of pertinent to nephrology bullets of physical examination according to the 1997 guidelines.

Medial Decision Making Block of Medical Documentation

Medical Decision Making (MDM) is an “Assessment and Plan” part of medical documentation reflecting presenting problems and their status, summarizing medical data supporting diagnosis or planned investigations, and treatment options [3,4,9]. Notwithstanding, in terms of billing and coding, MDM is a fundamental part of medical encounter determining its overall complexity; therefore, dictating the required levels of History and Physical examination in the corresponding encounter. For a medical encounter with low MDM complexity, it would be inappropriate, nor practical, to perform the comprehensive History and Physical examination. Oppositely, if medical encounter has the highest level of MDM complexity and does not have appropriately performed and documented levels of History and Physical examination, the encounter would not qualify for the highest level of service resulting in lost revenues. In general, as MDM complexity of a medical encounter increases from straightforward to high complexity, History and Physical examination requirements also increase form brief to comprehensive. However, most new encounters and consultations related to nephrology specialty would qualify for at least moderate level of MDM due to general complexity of patients with acute and chronic kidney diseases, and, therefore, would require comprehensive History and Physical examination documentation.

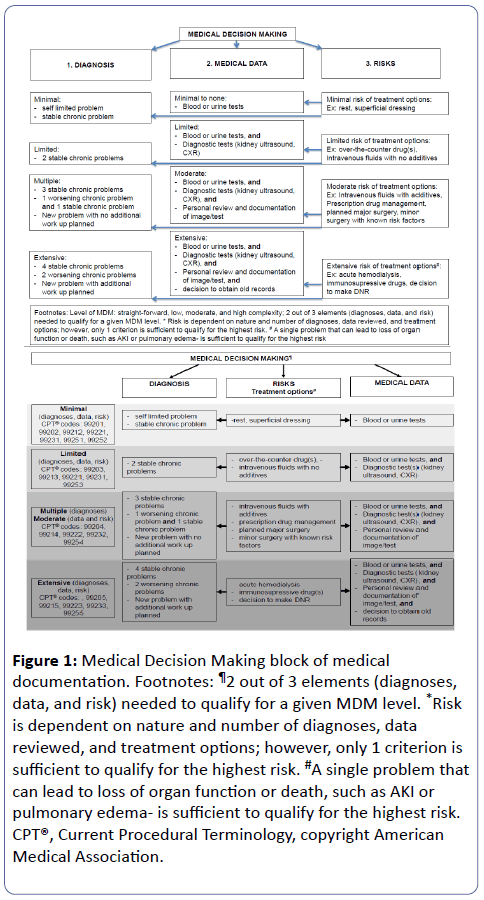

MDM is based on 3 elements: (1) number, type and status of presenting problems/diagnoses, and, therefore, number of treatment options that are needed to be considered; (2) complexity of medical data that are required to be reviewed and analyzed; and (3) risk(s) for the patient, in terms of morbidity and mortality, associated with presenting problem(s), diagnostic procedures, and/or treatment options. The risk of MDM circles back to the nature and complexity of presenting diagnose(s) and medical data for review, and also evaluates treatment complexity, with all 3 (diagnoses, data, treatment) becoming sub elements of the risk. Each of MDM elements is further subdivided into different levels of complexity, and when combined together they determine overall level of MDM. Figure 1 summarizes each of these elements and provides several examples. We also recommend reviewing risk table in the CMS guidelines [9]. There are 4 levels of MDM: straightforward, low complexity, moderate complexity and high complexity. In order to qualify for the highest level of MDM, 2 out of 3 elements (for example diagnosis, and risk, or diagnoses and data reviewed) are needed to support a particular level of MDM. When physician determines the overall risk of medical encounter, only one sub element is sufficient to qualify for the highest risk. For example, when patient presents with 1 medical problem, which poses risk for the loss of organ function or even patient death, such as AKI or pulmonary edema that makes the medical encounter as having the highest risk, regardless of planned interventions or diagnostic work up.

Figure 1: Medical Decision Making block of medical documentation. Footnotes: ¶2 out of 3 elements (diagnoses, data, and risk) needed to qualify for a given MDM level. *Risk is dependent on nature and number of diagnoses, data reviewed, and treatment options; however, only 1 criterion is sufficient to qualify for the highest risk. #A single problem that can lead to loss of organ function or death, such as AKI or pulmonary edema- is sufficient to qualify for the highest risk. CPT®, Current Procedural Terminology, copyright American Medical Association.

“Assessment and Plan” reflecting MDM can be documented together or as a separate “Assessment” and a separate “Plan”. It is important to use diagnoses supported by the ICD codes for the correct documentation and to facilitate reimbursement. For the nephrology trainees, it is critical to invest time to research and study what diagnoses, related to nephrology, are “billable” and in what order. For all inpatient and outpatient encounters, if patient with chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 1-4 have concomitant diagnosis of hypertension (HTN), the primary diagnoses for that encounter should become HTN with CKD stage 1-4 (403.90) and the secondary diagnosis is CKD (585.x). In patients with ESRD and HTN, the primary diagnosis would be HTN with CKD stage 5 (403.91) and secondary diagnosis is ESRD (585.6).

Time Based Encounters

Inpatient and outpatient E/M services performed by nephrologists have average times associated with these services; nevertheless, fulfillment of time component is typically not required for coding [8]. Most commonly, when choosing an appropriate level of service, the determining factor is how key elements of medical documentation (History, Physical examination, and MDM) match in complexity. However, when the majority of time during encounter is spent on counseling and coordination of care, this time can determine the level of service, irrespectively from key elements of medical documentation. For inpatient encounters, all time spent during patient care such as during interview, examination, and unit/floor time during discussion of patient care with other physicians or nursing staff is included into “time” component. For outpatient encounters qualifying for level of service based on the time component, more than 50% of time during encounter should be spent face-to-face with the patient or family. An exact timing and a description nature of counseling and/or coordination of care must be documented in the medical documentation in time-based encounters. For example, time requirement for level 3 (99213) and level 4 (99214) outpatient follow-up visits is 15 minutes and 25 minutes, respectively. The AMA publishes average time guidelines for different E/M services [8].

Dialysis Documentation

Patients with kidney diseases may require dialysis (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis) for AKI or ESRD. Dialysis procedure for AKI and ESRD can be both rendered and reimbursed in inpatient setting. Presently, in outpatient setting, only dialysis treatments for ESRD can be reimbursed. Starting 2017, Medicare will start providing payments for outpatient dialysis that is performed for AKI indication. CPT® codes for inpatient hemodialysis include 90935 (single evaluation during hemodialysis procedure) and 90937 (repeated evaluations during hemodialysis procedure). 90945 and 90947 are CPT® codes for single and repeated evaluation during dialysis procedure other than hemodialysis, such as peritoneal dialysis or continuous renal replacement therapy. As oppose to initial and subsequent hospital visits, there are no specific requirements as to what elements of History and Physical examination should be included into inpatient dialysis encounters. Dialysis note should include a reason for the dialysis procedure, a statement that a patient’s evaluation occurred during dialysis with the exact time of evaluation. In addition, patient’s tolerability of procedure needs to be noted. If billing codes for the repeated evaluation are used, then it is necessary to document the exact time of each evaluation and to state specific reasons as to why repeated evaluation was required, and what changes, if necessary, were made to the dialysis prescription.

Physician payments for care of outpatient ESRD patients is made under Monthly Capitation Payment Method (MCP) that was introduced by the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) [10]. Under this method, practitioners can be paid based on number of face-to-face visits rendered during calendar month to in-center hemodialysis patients (CPT® codes 90960- 4 visits, 90961- 2-3 visits, 90962- 1 visit), or one monthly payment (CPT® code 90966) for home dialysis patients irrespective of number of face-to-face visits. Evaluation of dialysis patient can occur in dialysis facility or physician’s office. In the latter case, the medical documentation about dialysis patients should be accessible in dialysis clinic. At least one face-to-face visit every 3 months should occur during dialysis (for in-center hemodialysis patients) to evaluate dialysis access and to determine that patent tolerates procedure well. The required elements of History and Physical examination for outpatient hemodialysis documentation are less defined. However, the initial monthly visit, which is also called a “comprehensive” visit, needs to include assessment of the following areas based on CMS conditions for coverage: (1) diet and nutrition, (2) whether current mode of dialysis is appropriate, (3) assessment of dialysis access, (4) preliminary assessment of candidacy for transplantation, (5) assessment of dialysis prescription and dialysis adequacy, (6) assessment and treatment of anemia, (7) assessment and treatment of chronickidney disease mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD), including levels of phosphorus and parathyroid hormone, (8) evaluation of dialysis related complications such as neuropathy and arthropathy, (9) assessment of volume status, (10) assessment of blood pressure control [10]. Subsequent dialysis visits are called “limited”; however, they also should include brief assessment of one or more of the areas listed in the comprehensive assessment.

Conclusion

It has been shown that physicians spent on average between 26.6%-31.0% of their working time on medical documentation [11,12]. However, recent report from the Department of Health and Human Services found that up to 55% of submitted claims for E/M services were inappropriately coded in 2010 [6]. The majority of coding error resulted in inappropriate coding of the level of service (incorrect upward -26% or downward -15% coding), but also 12% of clams had insufficient medical documentation for the requested level of service. This highlights the need of continuous education of physicians about medical documentation. The 3 key components determining levels of E/M service include History, Physical examination, and Medial Decision Making. For the initial encounters (inpatient and outpatient), all 3 key elements should satisfy the E/M requirements for that service; while, only 2 of 3 key elements (one of them MDM) are needed to qualify for a given E/M service for all subsequent visits. The “correctness” of medical documentation is judged by its quality and not by quantity of documented information. Importantly, all rendered services must be appropriate and medically necessary. Lastly, practice and feedback from biller/coders are necessary components of “polishing” medical documentation skills.

References

- Gillum RF (2013) From papyrus to the electronic tablet: A brief history of the clinical medical record with lessons for the digital age. The American journal of medicine 126: 853-857.

- Teichman PG (2000) Documentation tips for reducing malpractice risk. Family practice management 7: 29-33.

- https://wwwcmsgov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/95Docguidelinespdf

- https://wwwcmsgov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/97Docguidelinespdf

- https://wwwcmsgov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12pdf

- https://oighhsgov/oei/reports/oei-04-10-00181pdf May 2014

- CMS (2014) Evaluation and management services guide.

- Hill E (2008) Time is on your side: Coding on the basis of time. Family practice management 15: 17-21.

- https://wwwcmsgov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/eval_mgmt_serv_guide-ICN006764pdf

- https://www.Cms.Gov/regulations-and-guidance/guidance/manuals/downloads/clm104c08.Pdf.

- Ammenwerth E, Spotl HP (2009) The time needed for clinical documentation versus direct patient care. A work-sampling analysis of physicians' activities. Methods of information in medicine 48: 84-91.

- Fuchtbauer LM, Norgaard B, Mogensen CB (2013) Emergency department physicians spend only 25% of their working time on direct patient care. Danish medical journal 60: 4558.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences